“Science has been deleted from the Paris Agreement!”

Variations of this headline dominated the coverage of SB50 negotiations in Bonn.

The idea began early in the week when Saudi Arabia raised procedural concerns with the agenda item relating to the IPCC Special Report on 1.5, which was published in October last year.

The Saudis said that the topic should be discussed under an existing agenda item, not a new stand-alone agenda item. After some back-and-forth, the SBSTA chair proposed that Parties have a “substantive” exchange of views on the topic, and conclude the agenda item at that session in Bonn. Everyone agreed.

But then the headlines came.

Before going any further it must be said for the avoidance of confusion that the Kingdom has spent many years and millions of dollars undermining the climate science of the IPCC, and making sure negotiations in the UNFCCC do not set ambitious mitigation goals.

This is unsurprising for a country whose economy is wholly based on oil. They are trying to buy time.

But for many complex reasons they have been made into the sole villain of a long-running play with an abundance of villains, including some truly evil geniuses.

For example, the United States had in fact opposed the actual IPCC Special Report back in October…

And again, along with Saudi, Kuwait, and Russia, in Poland last December…

Yet this time around it was only Saudi who grabbed the headlines.

Very little of the coverage explored the reasoning behind some of the statements. Thankfully Third World Network does that, and reports what exactly was said by whom, so you can judge for yourself.

An unfortunate reality that has been caught up in the “science denialism” is the fact that there are in fact gaps in the IPCC reports. The IPCC readily acknowledges this. It is not a controversial statement, nor should stating it serve to undermine the basic findings of the IPCC.

In fact, science, and in particular climate science, is always political. From the selection of authors, to decisions about what qualifies as acceptable literature to peer-review, to the negotiation of the summary for policymakers, the entire process – like any aspect of life – is political. The IPCC is not immune from assumptions which are anything but neutral, including assumptions built in to the models about how much we will have to rely on certain unproven technologies…

None of this changes the fact that the IPCC is the best available science.

What’s not clear is that a failure to enthusiastically welcome IPCC under the relative insignificance of a stand-alone SBSTA conclusion actually… matters.

It’d be nice, but what matters more is what countries do. Is their NDC in line with what the IPCC says is required to remain below 1.5 agrees warming?

Is the money that rich countries are putting on the table commensurate with the financial needs of poorer countries to deliver their NDCs?

It is interesting that there was not so much coverage of stories about how rich countries conspired to delete references to conflicts of interest, or how peddlers of false solutions kept forcing their free-market ideology down our throats. And we have to ask why were these issues trumped by procedural bickering about a report which has already been written, and its negotiated summary widely circulated.

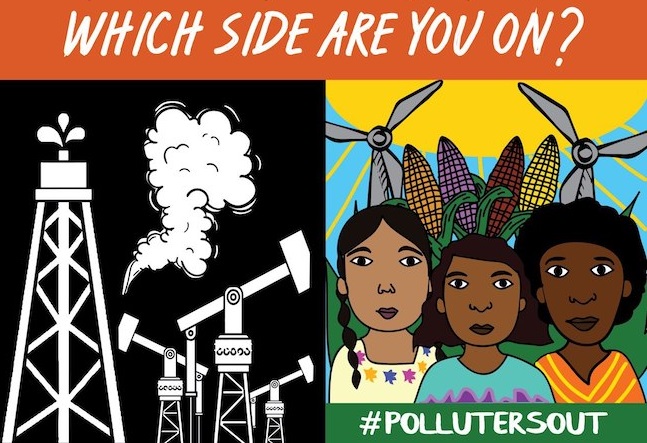

Or why the headline for every single news outlet was not this:

Or this